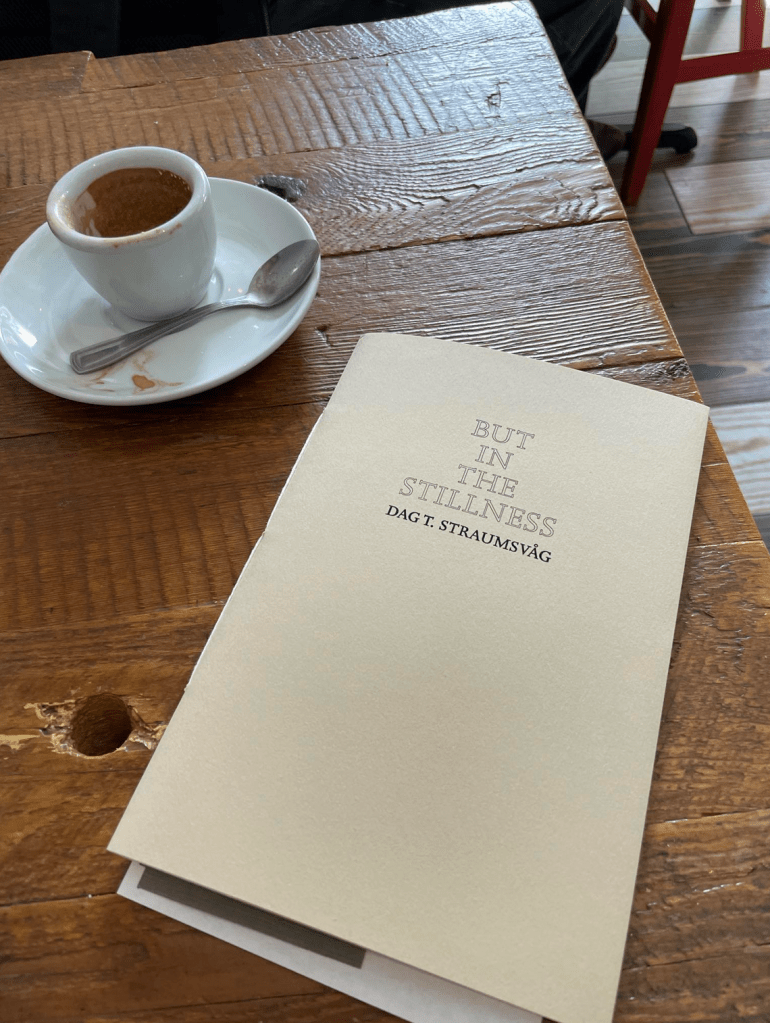

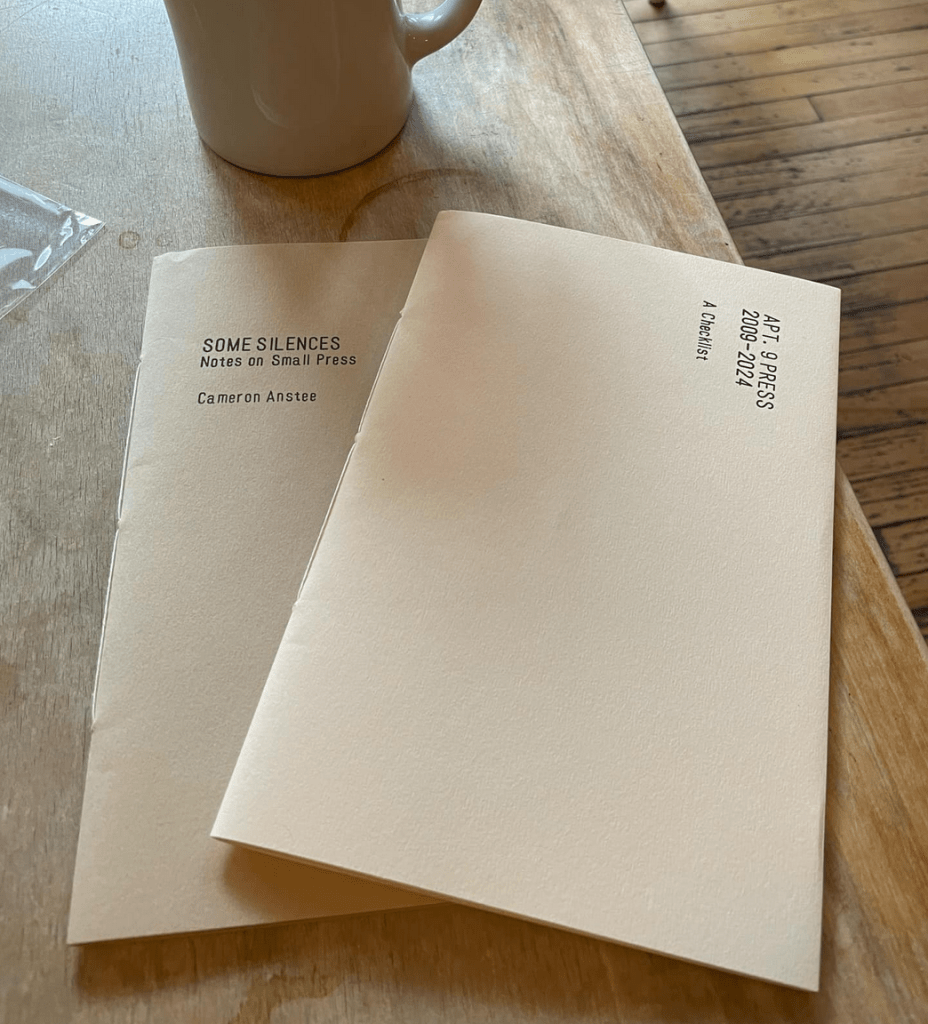

Cameron Anstee, Apt. 9 Press 2009-2024: A Checklist. Ottawa, Ontario: Apt. 9 Press, 2024, 80 copies.

–, Some Small Silences: Notes on Small Press. Ottawa, Ontario: Apt. 9 Press, 2024, 80 copies.

apt9press.com

A chapbook press lasting 15 years is certainly reason to celebrate and Cameron Anstee has done it with style, releasing two Apt. 9 Press titles to mark the occasion. They both strike me as essential for anyone with an interest in very small press publishing.

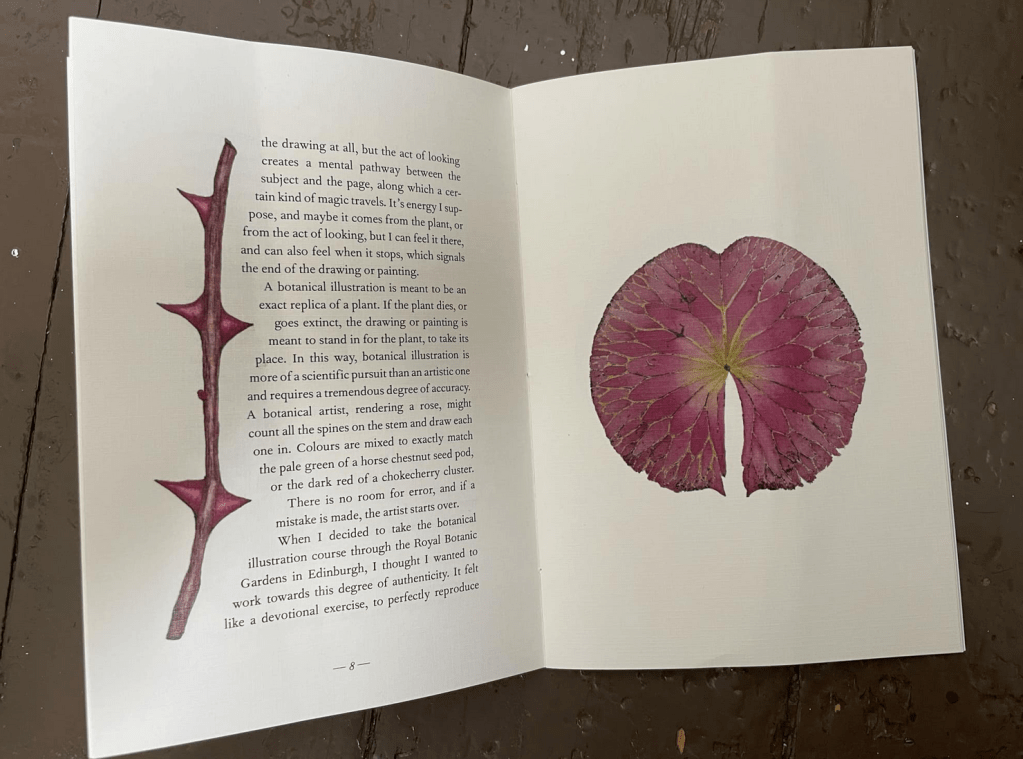

I am very glad to have the first, a checklist of publications, even if (as Anstee writes) it may be missing a few things. The introduction gives a brief history of the birth of the press, and informs us that his attractive chapbooks are still printed on a $100 laser printer. (The covers are often rubber-stamped.) What follows is an annotated list of fifty-two chapbooks, 2 proper “books,” two folios, twelve broadsides and leaflets, and ten titles under a separate imprint. I wish that I owned the first title, Justin Million’s Guzzles from 2009, both because I like Million’s work and, well, just because. “This was the first manuscript solicited,” runs the accompanying note. “I made proof after proof in different formats…trying to figure out what I was doing, what I wanted to do.” Million was also one of the volunteers who wine-stained the cover of Leah Mol’s And I’ve Been Living Dangerously (2011) on a night that “One of our cats escaped” and everyone “walked to the Ottawa River and watched fireworks being shot off”. These lovely bits remind us that for some making chapbooks is just a part of everyday life.

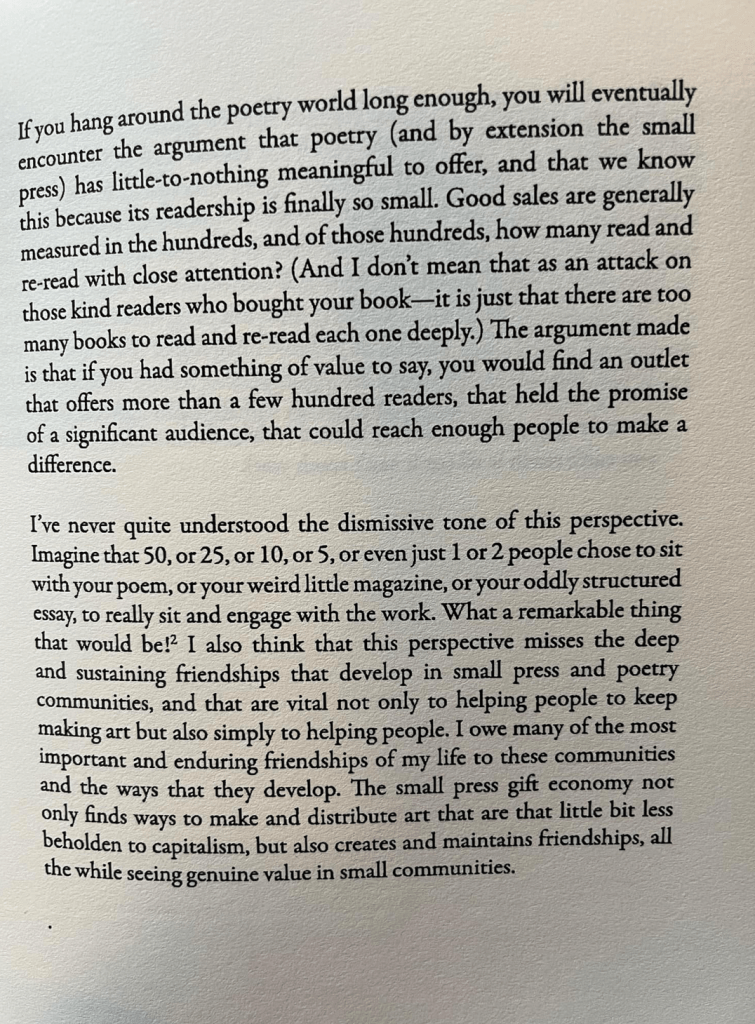

The second title, Some Silences, is Anstee’s meditation on fifteen years as a publisher. In it he is honest about the reach of a small press while modestly asserting its value:

Anstee tries to de-romanticize the act of publishing poetry when he confesses that “The ego side of it is hard—continuing to make things…while knowing it will meet silence whether this year or another.” But he fails to take out all the romance, both for himself and for us. Publishing links him to a tradition he highly values and hopes will continue after his own work is done. The small number of readers—well, it might sting sometimes, but it doesn’t take away from the one or two or three who discover an Apt. 9 title and find something meaningful in it. And for Anstee the act of making itself—printing, folding, sewing—must at this point feel like a necessary ritual.

The first title from the press that I bought was Michael e. Casteels’ Solar-powered light bulb and the lake’s achy tooth in 2015. In fact, it was the reason for starting this review blog. The latest are the two that I’m writing about here. I look forward to many more.