Dave Hickey, Safe Vehicules for a Dying Planet. London, Ontario: Baseline Press, 2021, 60 copies.

Dave Hickey is a ruminator, a thought-chewer who has no interest in hurrying himself to the end of a poem. He’ll take a subject—for example, the aptly-named “Ladder”—and see what he can make of it. One might have one “planted in the garden” yet be “no plant at all.” Rather than being of value for themselves, ladders are “purposeful” in allowing us to “climb their backs.” But then a ladder can be a useful metaphor as well, the rungs a sort-of calendar for marking off the time until the day of his daughter’s birth. There is the slight fear brought on by a swaying ladder, the dubious usefulness (in his opinion, not mine) of a kitchen stepladder, the relationship between a ladder and a narrow staircase. “And so to stand on a ladder is // to ask a good question with yourself” the poet says and one might think that he’s found his ending but no, there is still a thought or two to chew over and then a nice return to that young daughter who “looks up, / her mind wide // with the branches of trees.”

It isn’t surprising that Hickey likes a long line. He shuns the use of empty space, the short, broken phrase, the single word floating on white paper. It’s not ecstasy that he’s going for but something more quietly reflective and rational. How else will he come to the conclusion that a hammock is a “Public monument to rest” that belongs in the “museum of ordinary things”? How else will he bring in his natural sense of humour in a poem such as “Umbilical”:

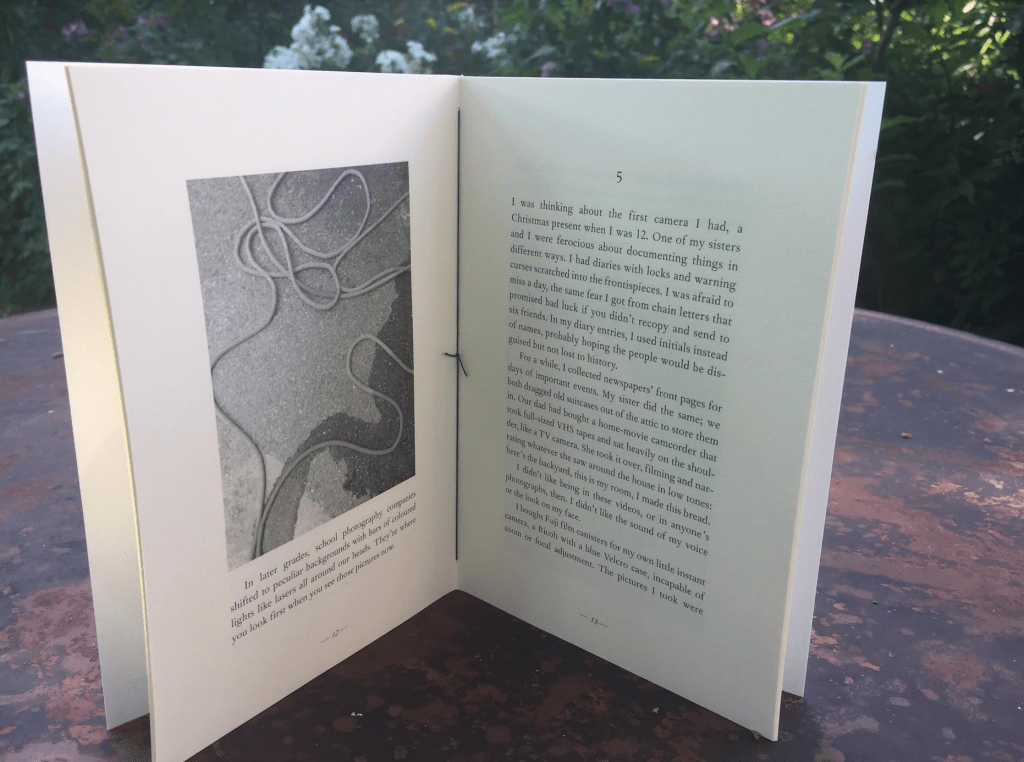

But what about things better left unbroken?

What about the traffic that speeds over a bridge

In a foreign city as a rainstorm approaches?

Bucharest, maybe? Have you been? Am I

Stalling? Are you? What kind of question

is that, anyway? How sharp are these scissors?

Who invented them? The scissors, I mean?

Can Dr. Scissors and I have a few words?

As can be seen from the above two-line stanzas (I have failed to put in the proper spacing), these poems don’t always have the reflective quality of a man leaning on a barn door with a stem of grass in the side of his mouth. For every poem about “Sod” there’s another that somehow manages to combine that more leisurely style with an anxious energy. It might be simply the need to “watch so your daughter won’t trip into the ditch / as you move up the trail, and keep her close that that when cyclists approach at unnerving speeds you can still reach out and pull her back”. This from a poem (“Beehive”) that also insists “I want to be more present, you say to yourself,” invoking that tricky second person voice and showing the poet’s success and failure at the same time. Unless a seeming uncontrollable talent for free-associating actually is a form of being present.

These highly accomplished and readable poems perform a sort of high-wire balancing act, being particular and universal, thoughtful and near-panicky all at the same time. There is an evocative image in a poem called “Tarp” of the poet wearing “a thought over my head until it catches the wind”. I definitely want to be standing in that same field, seeing what the wind brings.