Helen Humphreys, In Conversation with the Wild: On Drawing Nature. Kingsville, Ontario: Woodbridge Farm Books, 2024, 100 copies.

https://thewoodbridgefarm.com/shop

Helen Humphrey’s books have shown her to be a quiet, elegant, thoughtful writer. And with a highly developed sensitivity to the natural world. I’m thinking, for example, of the sustaining beauty of birds in wartime in The Evening Chorus. So it is not surprising to discover that Humphrey herself is sustained by nature—more specifically by drawing the ordinary flora of her world.

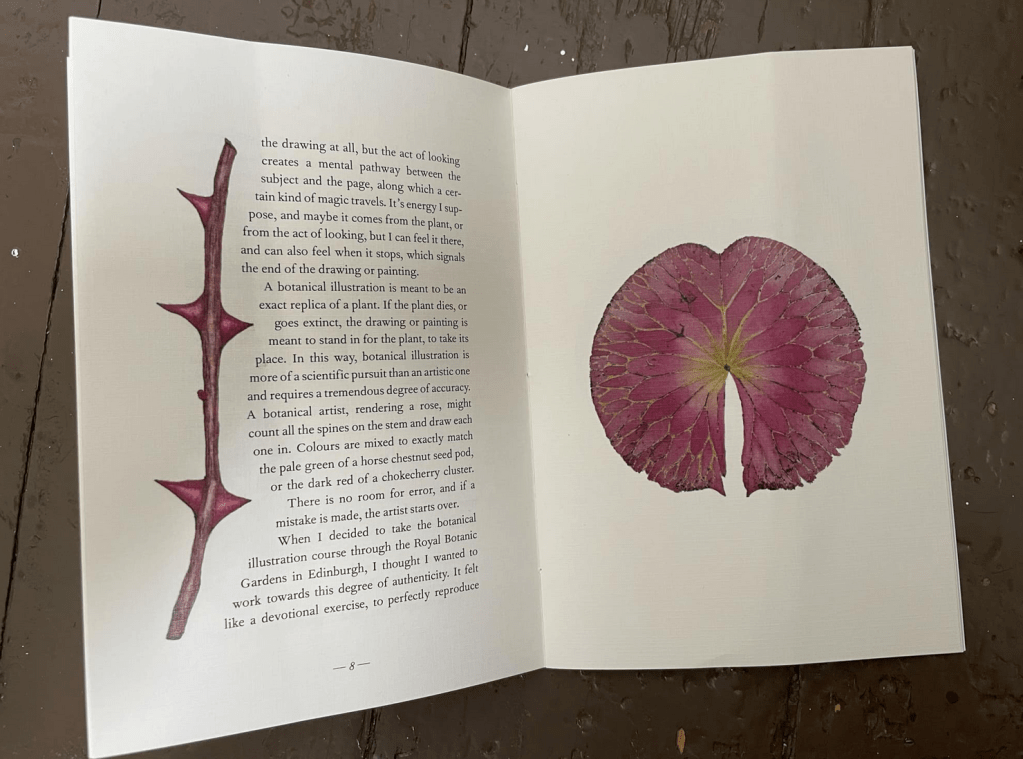

In Conversation With the Wild is the latest chapbook in the remarkable “Writers at Rest” series from Woodbridge Farm Books. Here authors are given space to write about their non-literary interests; for Helen Humphreys, it’s making botanical drawings of branches, acorns, seed pods, and, above all, waterlily pads. As someone who has found himself obsessed with various past-times over the years, I thoroughly enjoyed reading about Humphrey’s dedicated effort to learn to draw. How she took lessons, worked at it doggedly, and used her pandemic time to take a demanding botanical illustration course through the Edinburgh Royal Botanic Gardens. Also, how it became an extension of her own daily routine. “This summer I went swimming almost every morning in a lake just north of Kingston,” is how the essay begins. “I went with a friend and took my dog.” At the end of summer she “plucked a few waterlily pads from near the shore to take home to draw.”

Humphrey discovered that once taken from the lake, the waterlily pads began to suffer from “natural decay.” She learned to keep them submerged in water. She describes her attempts to draw them, when “the act of looking creates a mental pathway between the subject and the page, along which a certain kind of magic travels.” That magic she finds hard to explain, other than to call it energy that either comes from the plant itself or from the “act of looking” and here I wish she had pushed just a little harder to find more a precise understanding of what she’s feeling. On the other hand, I can sympathize with a desire to leave things a mystery.

The chapbook is generously illustrated and I can see that, while she is not a “professional” illustrator, Humphrey has become an accomplished amateur. And while she spends some time contrasting the experience of writing and drawing, her images remind me of her writing: careful, delicate, and subtle in their transformation of the real world into art.