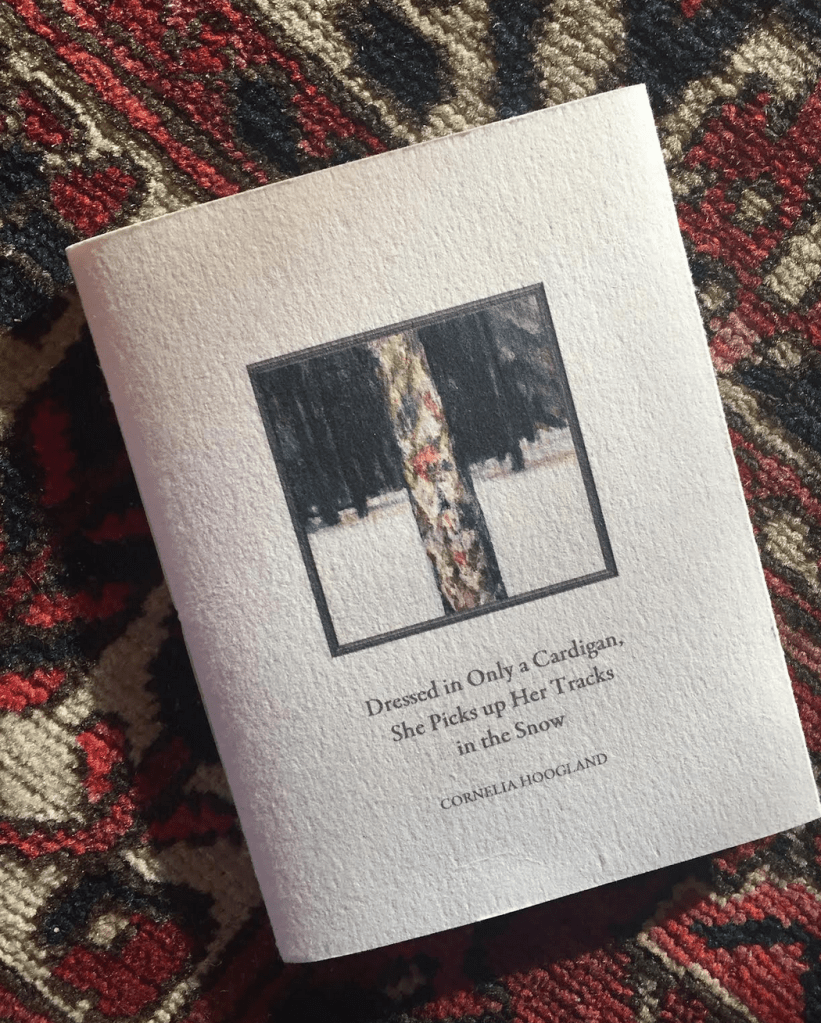

Cornelia Hoogland, Dressed in Only a Cardigan, She Picks Up Her Tracks in the Snow. London, Ontario: baseline press, 2021, 60 copies.

Without doubt there are particular challenges in writing about a parent, whether blamed and resented or loved and admired. The bad parent, while unfortunate in life, can make for some excellent dramatic material, while the good can easily lead the writer into the swamp of sentimentality.

Fortunately for her personal life, Cornelia Hoogland’s mother seems to have engendered only love and devotion from her daughter. And fortunately for the reader, Hoogland still manages to avoid being gushy in this series of twelve prose poems about Wilhelmina Grootendorst Van Rooyen (1924-2019). She has managed this by largely avoiding the mother/daughter relationship and instead by depicting Wilhelmina at the end of her life, as an independent but sometimes struggling woman in her 90s.

There are earlier moments in the life as well. Here is Wilhelmina’s father teaching her to swim by tying a rope round her waist and throwing her into the river. And here she is, a young married now, crossing on the Volendam from Rotterdam to Quebec City. The scenes that have the most effect, on me at least, are in old age; Wilhelmina needing help with her walker at the mall or talking to a photograph of her son even though she knows perfectly well that he has been dead for several years.

There’s a particularly nice moment (and a nice sentence) when she speaks to an old friend on the phone:

88 years of friendship, 68 years of newsy letters, gossip about a friend’s luckless marriage back home, but never malicious, everything kind; a husband’s new job, same pay but better hours; Wilhelmina’s bowling score, old news by the time Binky receives it, but who else can she tell?

I also liked the image of her and her visiting sister posing for a photograph as they “straighten their 90-year-old backs.” The poet cannot help turning into the daughter here: “Dear tiny vanities, long may you bind these women to the earth.” All right, a little gushing, but can you blame her?

There doesn’t seem to be any scheme or plan to the sequence; rather, the poet has used what has come to her. Wilhelmina’s mind drifts back to the Dutch landscape she left behind, or she is cozily watching Dr. Zhivago with a cousin. Here are a few lines from the penultimate poem, the one that comes just before “Wilhelmina in Heaven”:

Wilhelmina feels a chill. Sets her plate in the sink, follows her aluminum walker that glides over the floor on its stockinged feet. A Little Nap. Sits on her bed, removes her coat, places her glasses beside the clock. And now everything shrinks, every action, every thought, is spliced in half and again.

But Wilhelmina is never reduced for us. Her full life, her memories, the way she holds onto the people who matter to her—all of that remains fiercely present.